Beware Of Online Virginia Permits

If you took an Virginia Online CCW Class and were denied an AZ CCW Permit by AZDPS, we can help.

Our Online Blended Learning CCW Class WILL GET YOU A PERMIT!

Check our Reviews. Read our Frequently Asked Questions Below. Call us 7 days a week at 1-602-300-3550.

Obscure Concealed-Carry Group Spent Millions on Facebook Political Ads

One firm spent more than $2 million to advertise on the social network in the no-man’s land of digital political ads.

A company called Concealed Online spent more than $2 million on Facebook ads in the regulatory no-man’s land of digital political ads.

Obscure Concealed-Carry Group Spent Millions on Facebook Political Ads

One firm spent more than $2 million to advertise on the social network in the no-man’s land of digital political ads.

A company called Concealed Online spent more than $2 million on Facebook ads in the regulatory no-man’s land of digital political ads.

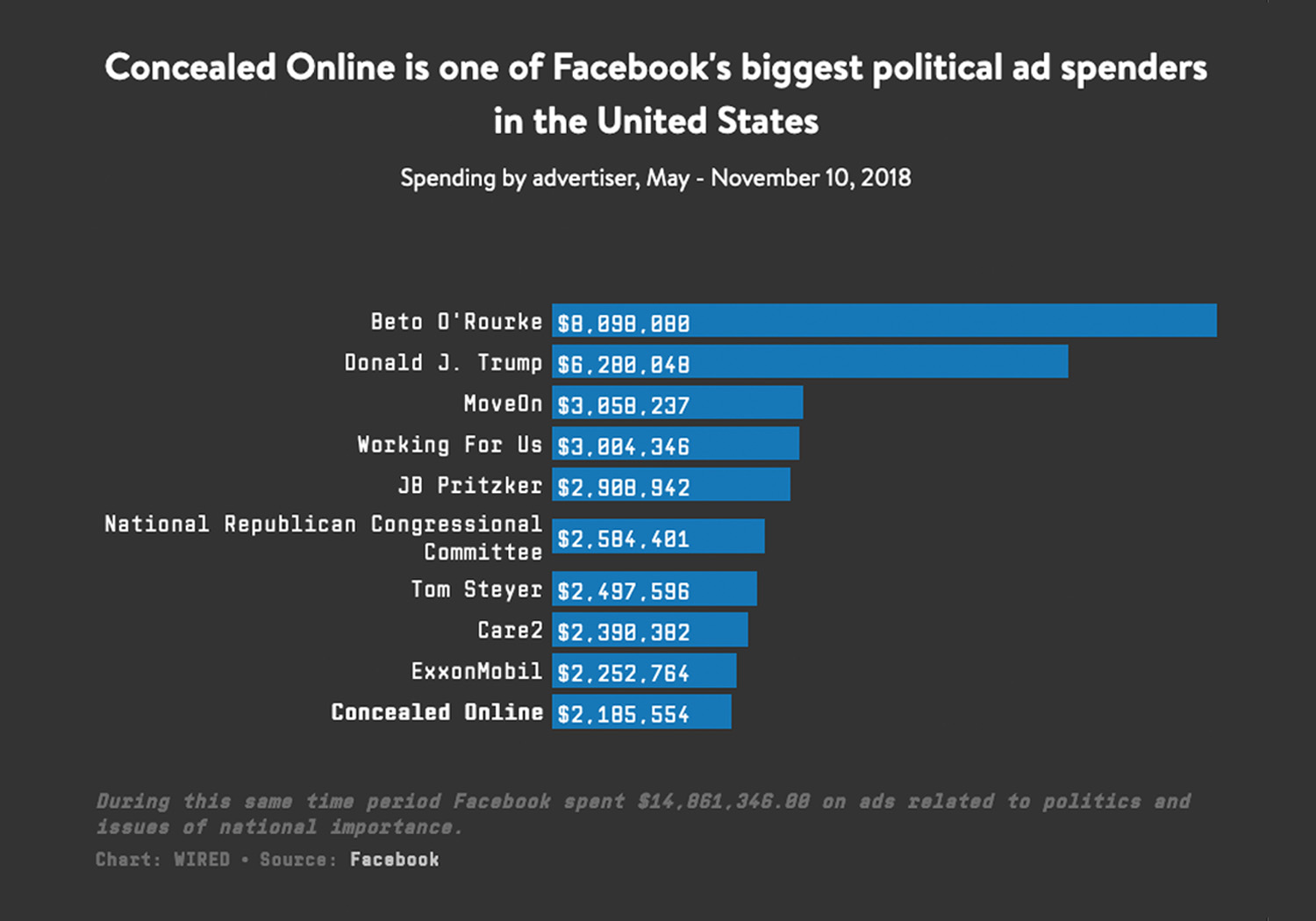

AMONG THE BIGGEST spenders on Facebook political ads during the recent midterm campaigns are some names you’d probably expect. There’s Beto O’Rourke, who lost to Ted Cruz in the Texas Senate race. There’s President Donald Trump—both his campaign and his super PAC. There are billionaires like J.B. Pritzker, incoming governor of Illinois, and Tom Steyer, the environmentalist leading the campaign to impeach Trump. And of course, there’s a multibillion-dollar oil giant, ExxonMobil. But tucked into that list, rounding out the top 10, is a name few have heard of: Concealed Online.

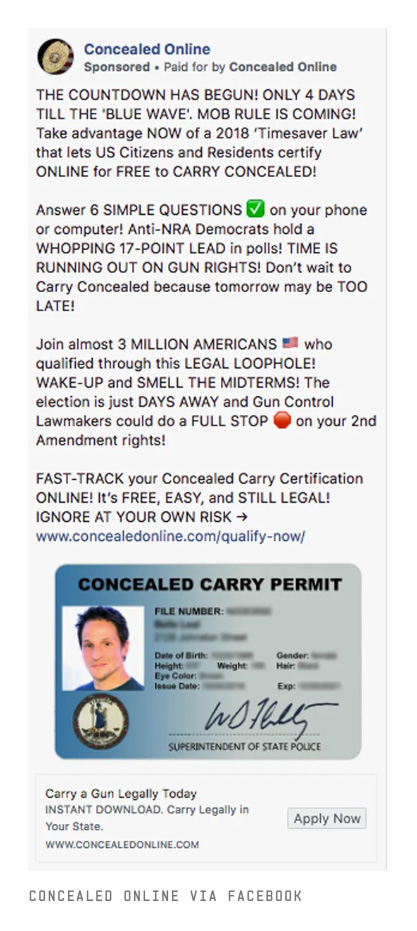

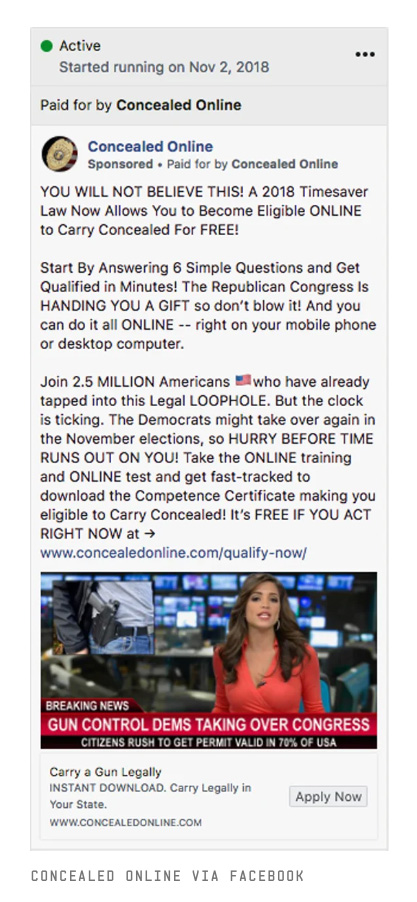

Since May, Concealed Online—a for-profit company that offers an online course and sells online certifications for concealed-carry gun permits in Virginia—shelled out more than $2 million on Facebook advertisements. That’s slightly less than ExxonMobil, and far more than well-known groups like Planned Parenthood. Its ads warn about the “blue wave.” “MOB RULE IS COMING!” read one series of ads before the midterm elections. And after: “IT’S ALMOST OVER! The Gun Control Dems are IN.” The messages are laced with heated political rhetoric, but they don’t advocate for political action. Instead, they seem squarely designed to gin up customers to make the company money. They urge Facebook users to “certify online for free to carry concealed” through its website. (The certificates cost $65 to download.)

Concealed Online doesn’t share much information about itself. The company’s website gives no indication of ownership; its address as of early November was a virtual office in Burbank, California. But after inquiries from WIRED, the company changed the address listed on its site to Walnut, a suburb about 20 miles east of Los Angeles. There’s no Concealed Online company registered with the California Secretary of State, while the website is registered to a business that buys domains on behalf of clients who don’t want their information disclosed. A legal complaint filed in the Northern District of California in February 2017, however, identifies OrionClick LLC as the parent company of Concealed Online.

WIRED reached out to Concealed Online through an email address on the company’s website. After WIRED received a response from Concealed Online’s lawyer, Karl Kronenberger, the company’s owner agreed to an interview if WIRED did not publish his name. The owner says he chooses to keep his identity private in part because he fears attacks by “crazies,” and in part because his personal politics are “the opposite” of the ones reflected in his ads. He insists he’s not a partisan actor, but an internet marketer, capitalizing on political events to make money.

“We’re opportunistic marketers, sure,” he says. “The point of the ad is to effect a purchase, not influence policy.”

Digital political ads exist in a regulatory no-man’s land. Where political advertisers on radio or television must file disclosures with the Federal Election Commission and include disclaimers about who paid for the ad, no such rules exist in the digital space, though some have been proposed. Even on TV, for ads that aren’t purchased by candidates or PACs, the FEC only requires disclaimers on so-called “electioneering communications,” which must be publicly distributed shortly before an election and include clear references to a specific candidate. But the digital gap allows anyone, regardless of motive, to run highly targeted, politically divisive ads with next to no oversight. With its ad archive, Facebook has tried to institute some transparency into the process. But Concealed Online’s multimillion-dollar ad campaign raises questions about how transparent that system really is.

Concealed Online launched in 2016, three years after Virginia started allowing people to take online courses to qualify for concealed carry permits. Those permits are recognized in states across the country, and even nonresidents of Virginia are eligible. The company’s owner saw a business opportunity in that. So he developed an online training course, where people can watch a video on gun safety, take a test, and instantly download a certificate of competency with a handgun for a fee. You can take the test as many times as you need, making it nearly impossible to fail. I passed without watching the training video and with no firearms experience to speak of. I purposely got questions wrong and still passed.

Once you pass the test, you can download a certificate for a fee, which can then be used by Virginia residents and nonresidents as part of an application for a concealed-carry permit in Virginia, one of the only states that allows online certification. On its website, Concealed Online specifies that the Virginia permit isn’t recognized in all 50 states and notes that it’s the customer’s responsibility to heed the laws where they live. But the ads WIRED saw don’t include those caveats.

Instead, they feature urgent warnings, like “The election is just DAYS AWAY and Gun Control Lawmakers could do a FULL STOP 🛑 on your 2nd Amendment rights! FAST-TRACK your Concealed Carry Certification ONLINE! It’s FREE, EASY, and STILL LEGAL! IGNORE AT YOUR OWN RISK.” Nevertheless, Concealed Online’s owner rejects the idea that this is in any way a political ad. “It all depends on the intent of the ad. What’s the call to action? 100 percent of the time our call to action is: Click here to buy our product,” he says. “The intention is to cause a sense of urgency to achieve more sales.”

The Better Business Bureau gives Concealed Online an F rating, in part because it has received 25 complaints—primarily from people who paid for the certificate only to find out that Virginia’s permits aren’t recognized in their state. The most recent complaint was filed last month. The Better Business Bureau opened an investigation into Concealed Online’s ads but has received no response. The company’s owner says Concealed Online sells certificates to people living in states like California and Colorado, which don’t accept Virginia permits, because they can use them when they travel to states that do.

Kronenberger, Concealed Online’s lawyer, asserts “My client didn’t do anything wrong. They followed the law.”

Concealed Online is not the only company leveraging the Virginia permit as a business model. Others like National Carry Academy and US Concealed Online have popped up in recent years offering similar online certifications. The Virginia State Police confirmed that the state accepts online certifications, but doesn’t endorse any particular program. But Concealed Online appears to be the only one that spent so substantially on Facebook in the social network’s political ad archive. From May through November 10, the company ran 12,961 ads at a cost of $2,185,554, according to Facebook’s archive report.

Concealed Online’s ads are included in Facebook’s political ad archive because they address an issue of national importance—namely guns. The company’s owner, however, argues his ads shouldn’t be listed alongside super PACs and political campaigns in Facebook’s ad archive, because their purpose is purely commercial and not ideological. In fact, he says business was better when it looked like Hillary Clinton was going to win the presidential election, because people were afraid that “everybody’s going to come take their guns.”

That may be, but in Facebook’s eyes, any ad that talks about guns—or immigration or abortion or any number of other political issues—is considered a political ad. There’s a reason for that. During the 2016 election, Russia’s infamous troll farm, the Internet Research Agency, ran ads focused on divisive political issues like race and immigration, often without mentioning a candidate at all. One page, called Black Fist, even posed as a commercial venture offering self-defense courses to black Americans.

Such ads wouldn’t trigger an FEC disclaimer, even if they appeared on television. But the backlash against Facebook and other platforms has been so fierce since 2016 that in its efforts to combat future manipulation, Facebook decided to include both candidate and issue-specific ads in its archive, which stores information on the advertisers and the ads themselves. The company requires these advertisers to go through an authorization process, which includes submitting their government-issued ID and a residential mailing address.

Concealed Online’s owner says he had no choice but to register as a political advertiser when Facebook instituted its new policies. Facebook wouldn’t run his ads until he completed an authorization process, which included sending a letter to his home to prove he was a US resident. But he considers Facebook’s new system to be an overreach. “Facebook made the rule. It’s not a law,” he says.

Facebook acknowledged that Concealed Online is an authorized political and issue advertiser. A spokesperson for Facebook said it has looked into Concealed Online’s ads and found that they don’t violate Facebook’s policies.

In a lot of ways, the ad archive does make political ads on Facebook more transparent. Before it, there was no way to see everything an advertiser was publishing, who they were reaching, or how much they were spending. Without the archive, Concealed Online’s ads would remain, well, concealed, except to those users who saw them in their feeds. Concealed Online is far from the only for-profit business swept up in the archive. Both Ben & Jerry’s and Penzeys Spices are also authorized political advertisers on Facebook. But the opacity of Concealed Online’s business also exposes a blind spot for Facebook and for the regulation of digital political ads in general, according to Ann Ravel, a UC Berkeley law professor and former FEC commissioner under President Barack Obama.

Despite all of the noise about protecting elections in Washington and Silicon Valley over the last two years, digital political ads remain largely unregulated. “The law doesn’t cover them,” Ravel says. “My opinion is that it should. This is the essence of where campaigning has gone now.”

Ravel adds Facebook’s archive is “not sufficient.” As the case of Concealed Online shows, Facebook’s database can tell you what entity placed the ad, but it reveals little about who’s really behind it. That’s an issue that’s hardly specific to Concealed Online. ProPublica recently reported on a dozen ad campaigns that appeared to be backed by oil giants hiding behind Facebook pages of different names. And reporters have proved how easy it is to deceive Facebook’s authorization system. Vice News recently tried to buy Facebook ads that were marked as “paid for by” 100 different senators. The ads never ran, but Facebook approved the disclaimers.

With millions of ads being placed in any given election cycle, it’s just tougher for tech platforms to vet each advertiser thoroughly. That makes the problem of transparency, which exists offline, too, all the more difficult to address online.

Democratic senators Amy Klobuchar and Mark Warner and the late Republican senator John McCain introduced legislation last year that would impose new disclosure standards on digital political ads, including ads related to “a national legislative issue of public importance,” like the ones Concealed Online runs. But that bill, the Honest Ads Act, hasn’t progressed.

“None of this is covered on the internet by any laws or regulations; no one has even attempted to consider the Honest Ads Act, and the FEC has done nothing,” Ravel says. “It’s really a bad portent.”

Instead, Facebook, Google, and Twitter have all devised their own systems of disclosure. But those systems operate differently and include their own distinct databases, which are still works in progress. They’re no substitute, Ravel contends, for unilateral standards on a federal level.

Facebook, for its part, says the fact that people are asking questions about what they find in the archive is a step in the right direction. During a meeting with reporters at Facebook’s New York office late last month, the company’s global politics director Katie Harbath was asked about ProPublica’s big oil investigation. “Before this they would never have even seen those ads,” Harbath said. But she herself noted that the issue of transparency in political advertising is a problem Facebook can’t solve alone. “There’s not a legal structure around some of this yet, particularly when it comes to issue ads and what they’re required to disclose,” she added. “We’re going to be limited somewhat in terms of what we, as Facebook, can do.”

Facebook is rolling out changes to reduce the spread of sensationalist content, which has traditionally gotten the most engagement on the platform. Whether that will have any impact on the effectiveness of ads like the ones Concealed Online runs is unclear. For now, Facebook remains a main source of customers for the company. As Kronenberger put it, “They’re using this language because it’s working.”

Main Source & Full Article: Written by Issie Lapowsky with Wired.com

SENIOR WRITER – Issie Lapowsky is a senior writer for WIRED covering the intersection of tech, politics, and national affairs. Lapowsky covered startups and small business as a staff writer for Inc. magazine before joining WIRED, and before that she worked for the New York Daily News. Lapowsky received a bachelor’s degree.